PCOS and Hair Loss: what’s really going on?

The causes of hair thinning and hair loss

Hello everyone,

Sometimes women with PCOS get excessive hair, but sometimes things flip and we might see hair thinning and hair loss.

This can have quite a few causes so let’s go through them and identify what can we do to deal with this unpleasant symptom. They are:

Nutritional deficiencies

Hormonal impact

Thyroid issues

Stress

Genetic disorders/Autoimmune disorders

Infections of the scalp

The patterns of where we might be losing hair can also give us a clue of what might be the reason behind the hair loss.

Lastly, we discuss solutions and hair oils that might or might not help.

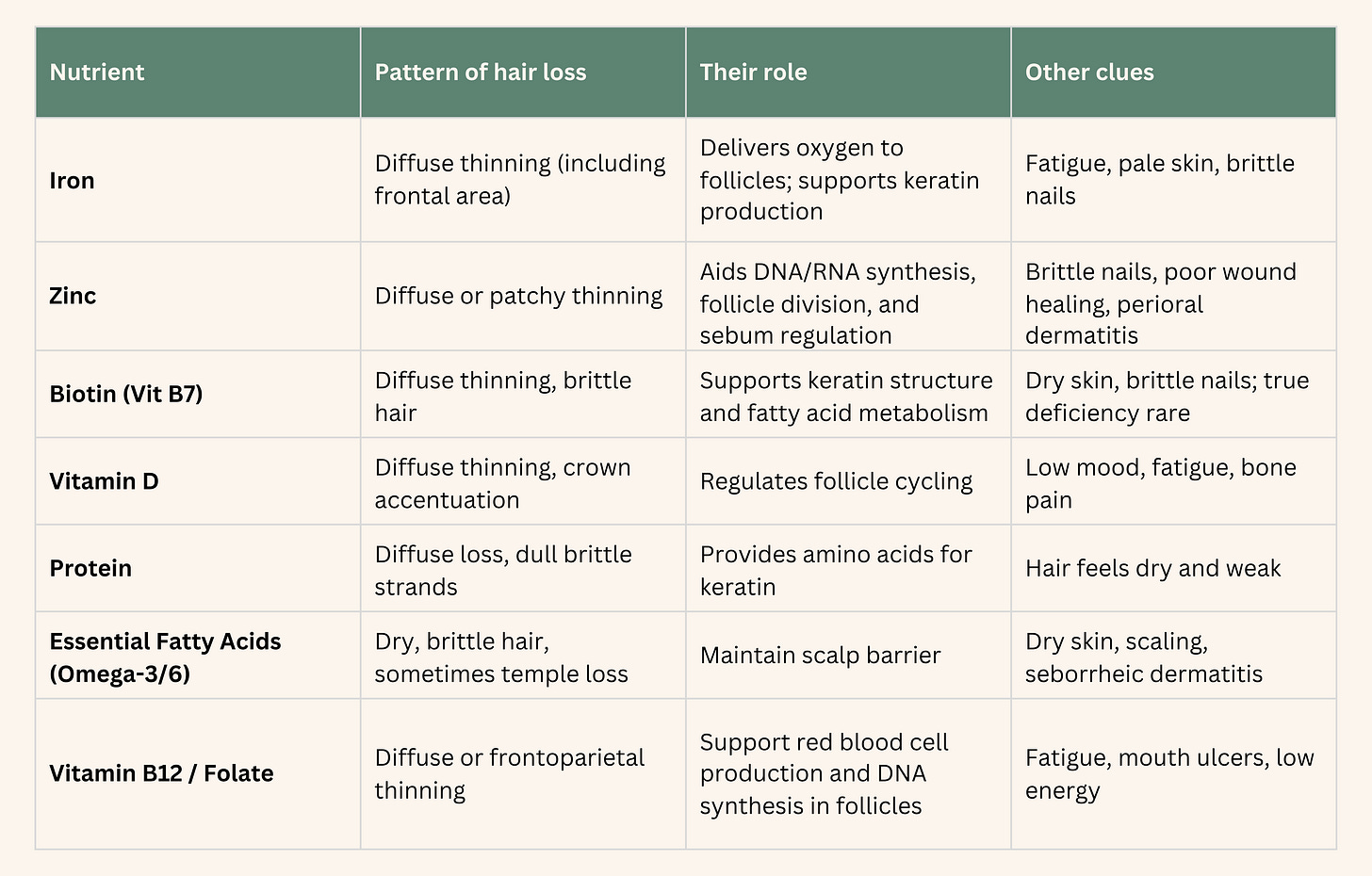

Nutritional Deficiencies

There are few key nutrients that we need in order for our hair to maintain its growth. The key ones are:

Iron - for this is very easy to get a blood test and know if you are low - there will also be other signs

Zinc - minerals are very hard to assess as they stay in tissues/not blood

Biotin - this can be tested for - brittle nails would also be a sign - to have a proper deficiency is very rare

Vitamin D - we all know how important this is for our health - supplementing during winter

Protein intake - watching our protein intake is important because amino acids are the building blocks of our health

B12 - this is a concern for vegetarian/vegan diets and those on Metform as it can impact B12 levels

Androgens

For hair thinning and hair loss, androgen can also be to blame, but what I found confusing was: how is possible that it can give me chin hairs but in the same time thin my hair?

The TL’DR is that all hair follicle have receptor for androgens. DHT, dihydrotestosterone, the more potent type of testosterone is often to blame for excess hair. However, interestingly this hormone has a different effect on the scalp hair follicules compared to those on the chest, chin etc. Here it turns terminal hairs into vellus hairs (the thin type of hair that we might see on our arms or face). This is because hair follicles in different body regions have different responses to androgens because of differences in both the number (density) and the type (sensitivity) of androgen receptors they have, and also because of the activity of enzymes like 5α-reductase that locally convert testosterone to DHT.

The challenge is to know if this is excess androgens is causing the hair thinning. In a detailed case series involving 109 women experiencing hair loss, only a third also showed high testosterone levels in the blood. This also why in PCOS diagnosis, we might display signs of high testosterone but not catch them in a blood test - I am one of those people.

The partial answer to why that might be is genetic variations. Some women seem to display certain variations that make the hair follicules more sensitive to DHT and its primarily in the enzyme conversions. Enzymes at the hair follicule levels are there to control how much of it is used.

One additional detail here that might give us a clue is that the hair loss typically will happen at the centre of the head, not in the front.

I have done a deep dive into how to lower androgens in this article if you are interested in learning that:

Thyroid issues

When we think that one hormone in the body does only one thing, think again.Thyroid hormones help hair follicles enter and stay in the anagen (growth) phase. Both T4 and T3 signal to the he cells that produce hair to multiply and resist cell death, promoting longer-lasting hair growth. In addition, hair follicles express thyroid hormone receptors (TRα and TRβ) and enzymes (deiodinases D2 and D3) which convert T4 into its active form T3 inside the follicle, allowing local action of the hormone regardless of blood levels. This is the same as for the testosterone.

Now you can imagine if these hormones are not behaving as expected, it will affect our hair.

In hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid), hair often becomes dry, coarse, brittle, and may fall out diffusely, including the outer third of the eyebrows. This is an interesting distinction and should be taken as a clue of what to look into further.

In hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid), hair often becomes dry, coarse, brittle, and may fall out diffusely—including the outer third of the eyebrows. This is due to slowed hair follicle cycling, longer telogen (resting) phase, and delayed onset of the anagen (growth) phase.

Stress

Chronic stress raises cortisol levels (we know that by now), which was shown in a 2021 study to keep hair follicle stem cells in a dormant “resting” phase longer. When stem cells are “switched off” by stress, new hair follicles aren’t created and old hairs shed without replacement. This is why some people might experinece hair loss or thinning as a result of traumatic experinece or from prelonged period of stress.

Auto-immune and genetic conditions

Alopecia Areata (AA): This is the most prevalent autoimmune cause of hair loss, resulting from an immune attack by lymphocytes against hair follicles during the growth (anagen) phase. The immune response disrupts hair follicle immune privilege, leading to patchy hair loss, and can progress to total scalp or body hair loss (alopecia totalis/universalis).

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): Hair loss in SLE can affect up to 50% of patients, mainly due to widespread inflammation and immune complex deposition affecting hair follicles.

Autoimmune Thyroid Diseases: Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Graves’ disease both cause hair loss by altering thyroid hormone levels and, through autoimmune inflammatory mechanisms, directly damaging the hair follicle.

Autoimmune Blistering Diseases: Pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigoid, and other blistering disorders can cause secondary alopecia due to autoantibody attack on the skin’s structural proteins, leading to hair loss and sometimes scarring.

Other autoimmune associations: Conditions like celiac disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and vitiligo are associated with increased risk of alopecia areata and related hair loss.

Genetic conditions:

Hereditary Hypotrichosis Simplex: Caused by mutations in genes such as CDSN, APCDD1, and RPL21, leading to progressive scalp hair thinning starting in childhood and often ending in near-total scalp baldness by the third decade; other hair and ectodermal structures are spared.

Genetic Alopecia Syndromes: Numerous syndromic forms of hair loss exist, where gene defects (e.g., FOXC1, LSS, structural hair disorder genes) lead to hypotrichosis, fragile hair, or patterned hair loss.

Genetic Predisposition to Autoimmune Alopecia: Family studies and GWAS confirm a strong genetic component in alopecia areata, with certain HLA haplotypes and immune-regulatory gene variants conferring susceptibility to autoimmune hair loss.

Infections

Infections of the scalp are probably a bit easier to distinguish. Infections usually cause local inflammation and visible changes to the skin or follicles, which help distinguish them from non-infective causes.

Tinea capitis typically presents with scaly patches, broken hairs, “black dots” (hairs snapped at scalp level), boggy swellings (kerion), and sometimes pus or crusting

Bacterial infections like folliculitis show follicular pustules, oozing, crusting, and tenderness, with clustered hair loss often accompanied by visible redness or swelling.

Yeast (seborrheic dermatitis) causes greasy scales and redness, with diffuse thinning mainly in densely affected areas.

These are easily diagnosable by a dermatologist.

Solutions

When it comes to what will work I think is important to understand the cause. A lot of these things come from within, so unless we identify and manag some of the driver, we will never get results. What is true it’s also that some of the genetic conditions there is not much to be done.

However, rosemery oil, coconut, argan, and castor oils have shown positive effects in studies. Rosemary oil is the most studied and popular.

In addition, there is a medication that is prescribed called Minoxidil which can help so I would discuss that with your dermatologist/GP if needed.

Other considerations

Lastly, there is also aging. It is a well known fact that aging leads to the thinning of the hair. Not much we can do there apart from making sure we eat well and take care of our hair as much as we can.

Post pregnancy is also common to experience hair loss. During pregnancy, high estrogen keeps more hairs in the growth (anagen) phase, resulting in thicker, fuller hair than usual. After delivery, estrogen levels fall rapidly, causing all the hair that was “held back” to shift into the resting (telogen) phase at once.

For similar reasons, menopause is also a time where women see differences in their hair.Not all women experience significant thinning; genetic predisposition, stress, diet, thyroid status, and scalp health also influence severity which means we have some power over it.

I hope you have enjoyed this deep dive and if this is something you are struggling with, don’t hesitate to get in touch.

Francesca

Ahmed, H., A. Kaliyadan and M.A. Alzahrani, 2019. Genetic Hair Disorders: A Review. International Journal of Trichology, 11(3), pp.107-117. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6704196/ [Accessed 5 November 2025].

Rodríguez-Tamez, S., Jarcho, J.A. and Chen, S.T., 2023. Hair Disorders in Autoimmune Diseases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 89(1), pp.1-10. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10015649/ [Accessed 5 November 2025].

Simakou, T., Butcher, J.P., Reid, S. and Nicolaou, N., 2019. Alopecia areata: a multifactorial autoimmune condition. Journal of Autoimmunity, 98, pp.74-85. Available at: https://researchonline.gcu.ac.uk/files/26910701/Alopecia_Publication.pdf [Accessed 5 November 2025].

Kassira, S., Tran, C., Castillo, D.T., Michelen, M., Limmer, A., and Qureshi, A.A., 2019. Alopecia in Autoimmune Blistering Diseases: A Systematic Review. Dermatology, 235(1), pp.6–15. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6751435/ [Accessed 5 November 2025].

Bhat, Y.J. and Keen, M.A., 2023. An Update on Alopecia and its Association With Thyroid Disorder. Cureus, 15(8), Article e10769472. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10769472/ [Accessed 5 November 2025].

Taieb, A. & Feryel, A., 2024. Deciphering the role of androgen in the dermatologic manifestations of polycystic ovary syndrome patients: a state-of-the-art review. Diagnostics (Basel), 14(22), p.2578. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11592971/ [Accessed 5 November 2025].

Messenger, A. G. & Rundegren, J., 2004. Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. British Journal of Dermatology, 150(2), pp.186-194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05785.x.

Muzumdar, S., 2023. Impact of thyroid dysfunction on hair disorders. Cureus, 15(8), e10492440. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10492440 [Accessed 5 November 2025].